Recently the Science Scribbler team hosted a livestream on Twitch to share the results from their most recent project, Synapse Safari. Read on to find out how all the hard work of Zooniverse volunteers is being used by researchers at the Rosalind Franklin Institute and the Centre for Developmental Neurobiology, King’s College London.

Why do we care about the synapse? What do we already know?

The Synapse Safari team are interested in looking at the changes in structure within the hippocampus during development. In this period, there is a huge amount of change in the brain, Juan Burrone explains: “Neurons begin to extend massive cable-like structures, dendrites and axons, that then contact each other and form connections with each other […] it’s highly, highly dynamic.”

In this key period of development and structural change, things can also go wrong: “There’s a whole number of neurodevelopmental disorders that we are particularly interested in studying as well that happen during this period of circuit wiring, during this period of high change in the environment”

To study these structural changes, the team use a high-resolution technique called electron microscopy. Specifically, they use a technology called serial block-face scanning electron microscopy (SBF-SEM). It works like this: after acquiring an image, a very thin and sharp knife slices away a thin layer off the top of the sample, exposing the layer beneath. This new layer is then imaged, and the process is repeated. By continuously imaging and slicing, a series of 2D images is generated. These images, when stacked together in sequence, can be reconstructed to form a detailed 3D volume of the original sample.

Using these electron microscopy techniques, the team have been able to start to create large-scale reconstructions of areas of the brain across development, to try to understand how the wiring process is happening.

Until now, Juan and Guilherme Neves had been painstakingly analysing their electron microscopy datasets manually. Going through each 2D slice of the 3D data volume and segmenting out between 10 and 20 dendrites and axons, mapping how they are connected to each other.

This would take them months – to generate the three coloured segmentations in the video below, Guilherme estimates: “If one person was working from, say, nine to five, it would probably take them many months, I would say, to be sure about all the connections.”

But, their hard work was worth it – analysing the morphologies of the segmented dendrites and axons at this “zoomed-out” level has allowed them to find order in the chaotic mess of neurones in these 3D datasets. Juan explains: “We found some really interesting distributions and properties in the way that synapses distribute along these dendrites, along the length of these dendrites. But we were lacking detail.”

Why did we need the Zooniverse?

The team wanted to look closer, within each synapse, to understand the structure, number, and arrangement of synaptic vesicles and mitochondria – organelles that are fundamental to how the synapse actually works. Juan explains this posed a huge challenge of scale: “If you imagine that each synapse contains say 100 vesicles per presynaptic terminal, and that a given neuron will receive in the order of 1000 or more synapses, and that there are billions of neurons in the brain. Then trying to reconstruct each vesicle within even just a few synapses is a lot!”

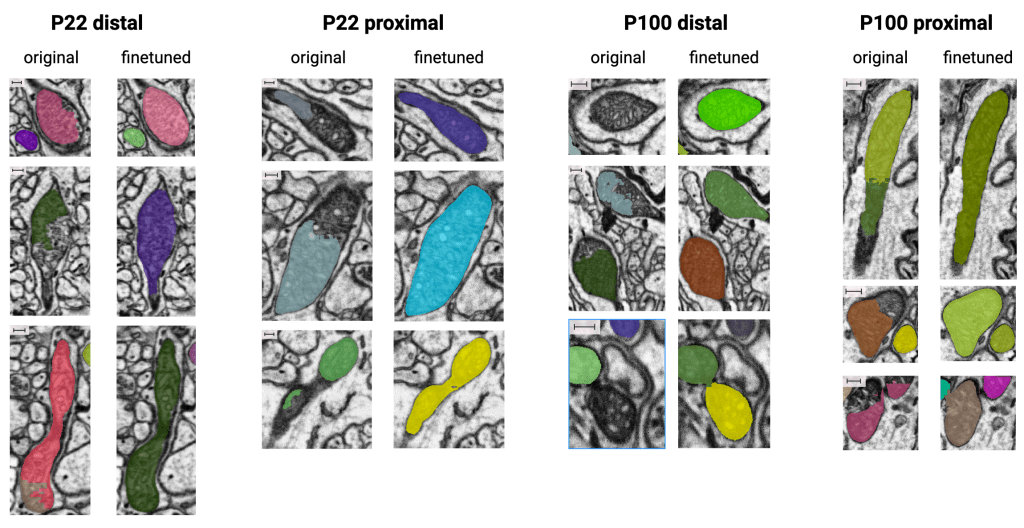

Here, the team first turned to computational methods and used a deep learning model called MitoNet[1] to segment the mitochondria, and a technique called template matching to segment the synaptic vesicles. Both of these techniques performed relatively well, which was great! But neither were perfect, so the team turned to the crowd to inspect and correct the output from these two techniques: a process called proofreading.

Crowd-powered proofreading

With the help of Zooniverse volunteers, the team was able to use the corrected segmentations of mitochondria to finetune the MitoNet model, and make it work better for the datasets, meaning fewer missed, fragmented, or poorly outlined mitochondria:

And by clustering the marks made by volunteers on missed or mistaken synaptic vesicles (SV), the researchers were able to get a huge number of correctly segmented vesicles:

Guilherme is very excited to investigate the outputs: “The first time synaptic vesicles were identified was like, 1962 or ‘63, but from then on, there’s been very few quantitative studies because they’re very difficult to segment. [With Synapse Safari] it became possible to start identifying them at scale, which is something that’s never been possible before. And we’re very excited for how this is going to work out in the future, and the kind of findings that we will be able to find.”

Unexpected discoveries!

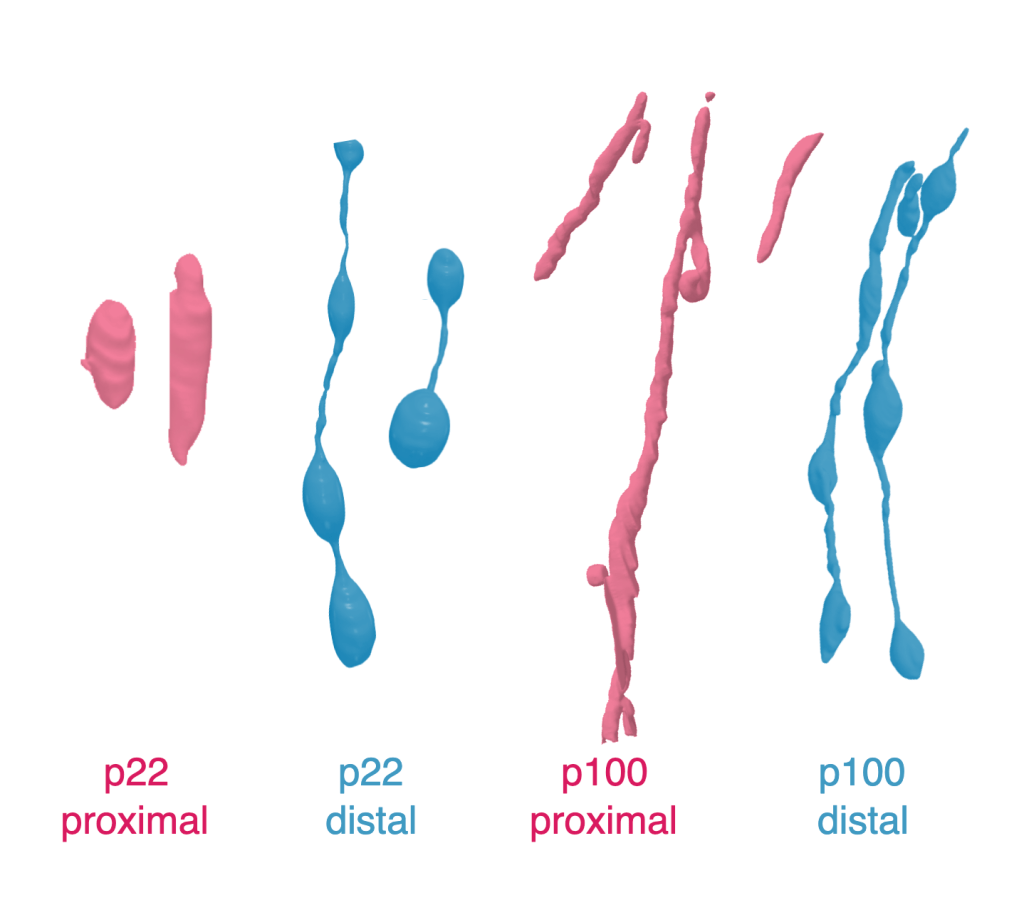

Thanks to over 1800 hours of volunteer effort, the team also uncovered some really interesting mitochondria morphologies. Chloe Cheng explains: “Our dataset is from two regions, one, distal, one proximal, meaning that one is further away from the cell body, and one is closer to it. And surprisingly, the mitochondria in the dendrites of these two regions look very different. So on the proximal sites, it’s more like what we would expect. We expect the dendritic mitochondria to be elongated and basically follow the dendrites, so they appear tubular. But on the distal side, in both ages, we find these weird beads-on-a-string structures.”

“This has been observed in in some other tissues, like heart muscle. It has been observed in the brain as well in Alzheimer’s patients. But I think we were the first to discover that there’s actually a distance related characteristic for these beads-on-a-string morphology.”

Rich data: a fabulous problem to have

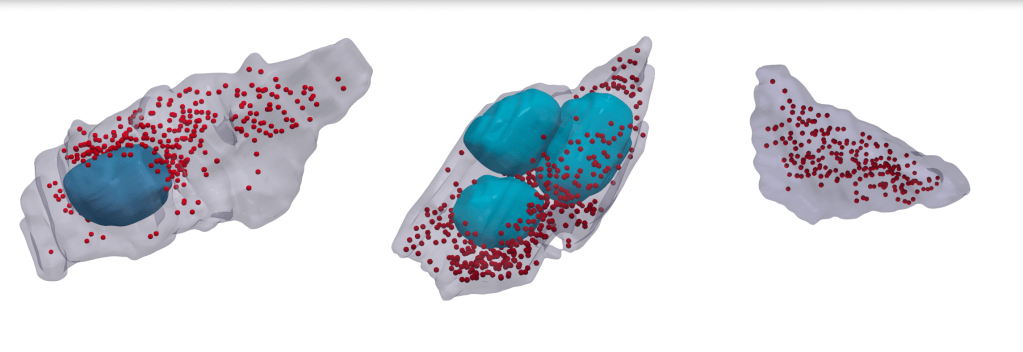

Together, the researchers now have a huge volume of annotated instances of mitochondria and vesicles – 10s of 1000s of synaptic boutons segmented, with the mitochondria and vesicles within as well. Here are three example boutons from the final segmentations, showing the mitochondria in blue, and synaptic vesicles in red:

Juan comments:“it’s beautiful – but it shows the heterogeneity that exists within these presynaptic terminals […] We really don’t know what the differences are of these mitochondria containing presynaptic terminals versus those that don’t, or the ones that have more mitochondria versus those that have fewer.”

“There’s a there’s a huge amount of information that we really haven’t tapped into, and, in fact, there’s a lot of analysis that we still need to do with this very rich dataset. This is a fabulous problem to have, but this is an incredibly rich dataset that we now have to try and analyse to try and get our heads together. What does it actually mean?”

What’s next?

The team are looking forward to combining their prior analysis of the distribution of dendrites and synapses with the new information gleaned from the segmentations of vesicles and mitochondria. Having this level of structural detail is key for understanding function as well, Juan says: We have this structural description of these vesicles and mitochondria within a presynaptic terminal. But what does it mean for the function, for the process of synaptic transmission, for the process of releasing neurotransmitter onto another neuron?”

Guilherme adds: “Having automated methods allows us to go back and analyse and mine the data that we already obtained, but also it has the added incentive of making us acquire more data […] which is something that we had almost given up on, because we thought that we couldn’t analyse even the data that we’ve acquired already”

Being wowed by the crowd

For Juan and Guilherme, this is the first time they’ve worked with citizen science. And Zooniverse volunteers have left a lasting impression:

Juan: “As somebody who was had never done this before and never worked with these kinds of sites before, I was very sceptical that it was actually going to work. [But] as soon as we put the first dataset out there, and things moved so fast, and we ran out of data – because everybody had already analysed all of our dataset within a few days – that’s when I began to realise that we were on to something, and that this really could be a game changer. And it turned out to be exactly that.”

Watch the full livestream here: https://youtu.be/sBCn58gk1gg

References

[1] Conrad R, Narayan K. Instance segmentation of mitochondria in electron microscopy images with a generalist deep learning model trained on a diverse dataset. Cell Syst. 2023 Jan 18;14(1):58-71.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2022.12.006.