For almost 15 years, ecologists at the Lincoln Park Zoo’s Urban Wildlife Institute have been studying elusive city wildlife using motion triggered cameras across the Chicago Metropolitan Area. From common raccoons to elusive foxes, this work has helped reveal where wildlife live across Chicago’s highly urban landscape. Since 2016 Zooniverse participants from around the world have supported this work by classifying hundreds of thousands of photos uploaded to Chicago Wildlife Watch, a Zooniverse project.

By comparing over 150,000 camera trap image classifications by Chicago Wildlife Watch participants to those made by zoo experts, a new study reveals just how valuable this participation is!

By far, Zooniverse participants were highly accurate at classifying empty images (99.6% accuracy!) and common species found across Chicago, such as white-tailed deer and squirrels. This is exciting news as these kinds of images make up the vast majority of project photos uploaded to Chicago Wildlife Watch and other wildlife camera studies (e.g. common species in their study areas).

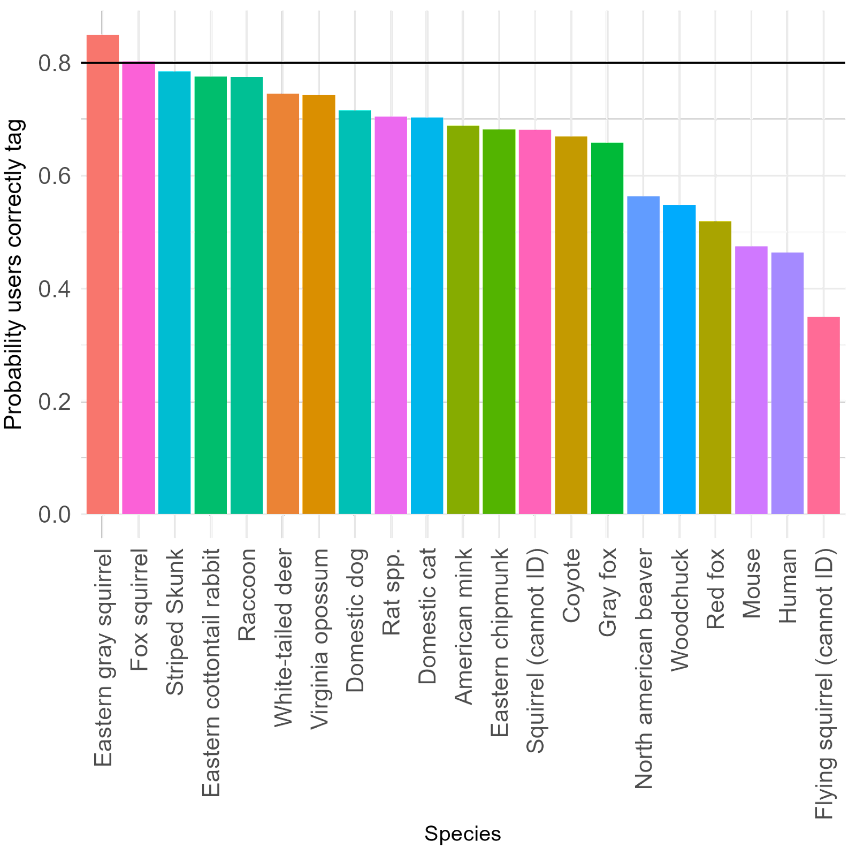

Figure 1. This plot displays how annotation accuracies vary across species found in and around Chicago.

What’s more, the Chicago Wildlife Watch team used these Zooniverse classifications to develop a Chicago-specific species classification model. This means the Chicago Wildlife Watch team can now estimate known sources of variation across images and participants, allowing them to easily analyze Zooniverse classifications and integrate these data into research on urban wildlife ecology. For example, the more agreement different users had on a single image (such as 7 Zooniverse participants agreeing there is a coyote vs. 4 Zooniverse participants tag dog and 7 tag coyote), the more likely that image would be classified correctly. Likewise, this study elucidated what species-specific classifications are acceptable ‘as is’ and which photos need to be verified by experts. Notably, expert verification is most important for rare species. In Chicago, species like gray fox and beaver are frequently misidentified, likely due to their rarity (only 11 and 14 photos were respectively collected in this study).

Figure 2. Sample of images uploaded to Chicago Wildlife Watch. (From left to right) American mink (Neovison vison), red fox (Vulpes vulpes), striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis), Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana), coyote (Canis latrans), and North American Beaver (Castor canadensis)

This work supports the notion that together, community participants and ecologists have power neither group has alone, and the more efficient these collaborations, the more we can accelerate scientific discovery and innovation! If you would like to read more about the results of this work, check out our article in Biological Conservation here. A big thanks to Zooniverse and all the participants that made this research possible!